Home » Myth » Stories » The Dagda’s Magickal Harp, Uaithne

This is a story of how the Dagda used a magickal harp named Uaithne to defeat an enemy army in battle. It comes from Celtic or Irish mythology. Is it an “official” myth? I actually don’t know. Is there really such a thing?

Regardless, it’s a story I read once, so I’m going to retell it here because I liked it.

Background

If you’re not familiar with the usual Celtic gods and goddesses, allow me to paint a quick picture for you.

This is me painting a picture, okay?

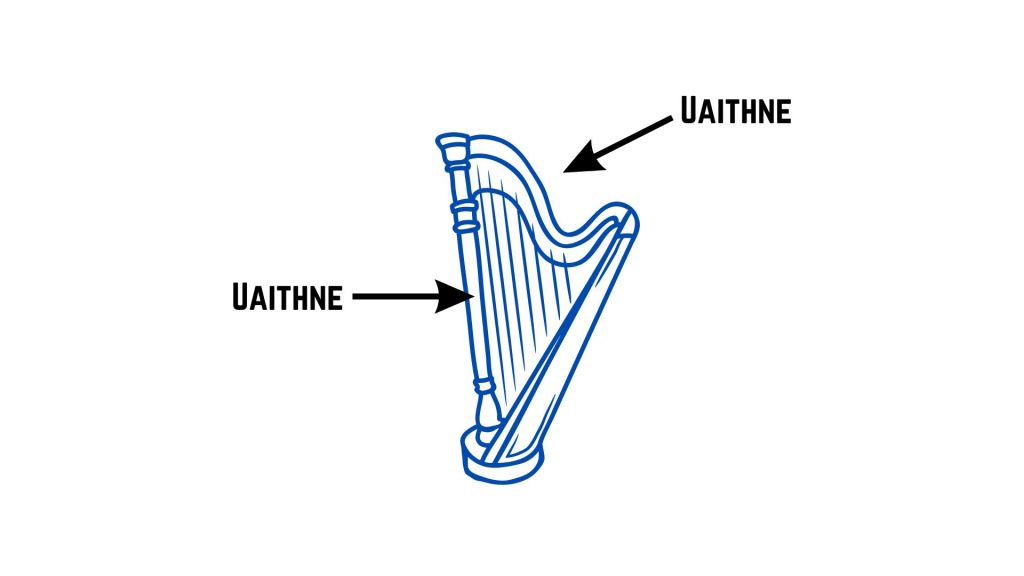

The Dadga is the “father” god of the pantheon known as the Tuatha De Danann, or “tribe of Danu,” as well as the hero of our story. He carried with him three magickal items – a club, a cauldron, and a harp named Uaithne, which was decorated in gold and jewels. The harp played music of joy, sorrow, and dreams and was capable of rousing any possible emotion. It was also said that Dagda put the seasons in their correct order by playing the harp.

The Dagda?

There aren’t really any actual depictions of Celtic gods and goddesses. Unlike the Greeks and Romans, they didn’t really make paintings or statues of their deities. You’ll just have to use your imagination.

Every good tale has a villain. The Fomorians are some sort of race of supernatural creatures. They’re the bad guys in our story and sworn enemies of the Tuatha De Danann.

That’s about all you need to know for now.

Weird Etymology

Old Irish is always a difficult language to contend with. In fact, a lot of Celtic and Irish myths can very quickly become confusing. By some accounts, Uaithne was the name of the Dagda’s harp — the instrument itself. By others, it was the name of the Dagda’s harper — as in, the person who would play the instrument.

Want to hear about future posts? Subscribe to get notifications delivered straight to your inbox.

The word Uaithne, which is pronounced something like “OOTH-neh,” was found in several different forms and possibly meant “childbirth.” According to eDIL (Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language), some older glosses give it as an equivalent word to “Orpheus,” who also played a similar stringed instrument, the lyre, in Greek mythology.

Uaithne’s multitude of spellings include Úaitni, Úathni, Uaithne, Uaithne, Uaithne, and nUaithne.

And according to the New English-Irish Dictionary, Uaithne can be a musical term meaning “concord or consonance” and can also refer to something that acts as a prop or support. That’s interesting, I think, because harps are consonant instruments that have a backbone of sorts.

But if we think of Uaithne as both a harp and a backbone, then I suppose the following graphic would also be true.

Finally, to make matters potentially even more confusing, the Dagda’s harp also had two other names: Daur da Bláo, “The Oak of Two Blossoms,” and Coir Cethar Chuir, “Four-Angled Music.”

The Story

At some point, the Fomorians and the Tuatha De Danann were engaged in battle. Actually, it was probably more like a war with several individual battles. These weren’t quick bouts, either — both armies would set up camp on their respective sides, fight during the day, and then return at night to recoup.

Each night, when they returned to camp, the Dagda would play his harp to celebrate and inspire his troops. The Fomorians heard this music from a distance and grew jealous… they wanted Uaithne for themselves!

A few Fomorian thieves snuck away from battle the next day, crossed enemy lines, entered the Dagda’s house, and stole Uaithne. They brought it back to their side and attempted to hide it away.

The Dagda’s army won the next battle. Once they returned to camp, they called out for music to celebrate, but alas, Uaithne was nowhere to be found. They quickly came to the conclusion that it had been stolen.

The Dagda gathered a few of his best fighters and snuck into the Fomorian camp. They went from house to house, under cover of night, searching for the harp. Finally, they found it chained to a wall.

When the Dagda saw his harp, which was bound to play only for him, he called out to it. At once, Uaithne broke from its chains and flew to the Dagda’s hand, killing several enemy soldiers in its path.

The Fomorians were startled and rushed to fight the Dagda. In response, he played the music of joy and the Fomorians dropped their weapons and danced. Once they recovered, they grabbed their swords and spears and rushed at the Dagda again. The Dagda played the music of sorrow and the Fomorians fell to their knees and wept. Again, they recovered and rushed at the Dagda once more. This time, the Dagda played the music of dreams… and the entire Fomorian army fell into a deep sleep.

The Dagda and his fighters safely returned to camp. The next day, they defeated the Fomorians. I’m sure there was lots of music to celebrate.

The end.

Okay, yeah, I may have potentially summarized, simplified, or embellished elements of this story. Please forgive me. This is the way it goes in my head. Either way, I hope you enjoyed it.

Further Reading

If you’re interested in learning more about Celtic myth, gods, and goddesses, you can check out some of these books.

Afterthoughts

The Celtic pantheon doesn’t really have a patron god or goddess of music. But that doesn’t mean music wasn’t important to them. Actually to the contrary, music was such a part of life that most of the gods had their own musical aspect. Dagda had his epic harp, Lugh was a master musician… but they also did other stuff!

I think we should apply that more in real life. Kids should learn more music in school. Music shouldn’t be something that only artists and musicians enjoy. It should be something that is accessible to everyone.

Those are my thoughts. What are yours? Tell me all about it in the comments.

Leave a comment