Anyone who has ever riffled through a medieval grimoire can tell you the pages are replete with instructions for forming circles of protection, but the symbolism of the circle stretches much farther back than the middle ages. Humans have been contemplating shapes since long before we properly understood the math behind them, and circles happen to be the only ones with a constant curvature. Naturally, they are easily lent to the ideas of perfection, infinity, unity, and more. You might even go so far as to say that πr² and 2πr are magickal formulae. As a number, the circle represents the concept of nothing, but as the egg, it represents the potential for everything. Many throughout the ages, including Carl Jung, have repeated the idea that divinity itself “is a circle whose centre is everywhere and the circumference nowhere,” but where did this notion first begin? If we step back through time, the earliest written evidence of the mysticism surrounding circles probably goes back to Ancient Egypt.

From Shen to Cartouche

To begin to understand the importance of the circle to the Ancient Egyptians, we first need to take a look at the Egyptian language. Their word for “encircle” was shen. Scholars have also discussed additional contextual meanings for shen such as “enchant” and “spellbind.” On a personal note, I find it rather fascinating that their ideas of encircling and enchanting might not have just been synonymous, but exactly the same word.

An amulet, circa 1254 BCE, featuring the falcon form of Horus carrying two shen rings. Photo by Rama, CC BY-SA 3.0 fr, Wikimedia.

The Shen Ring was a knotted loop of rope. It was often worn as a protective amulet. In hieroglyphs, this symbol was drawn as a circle with a tangent line. It represented concepts like protection and eternity. In certain circumstances it could even be interpreted to mean “everything encircled by the sun” and by extension, the pharaoh’s dominion over it. Egyptian artwork sometimes shows the falcon form of Horus carrying a shen ring above the head of a pharaoh, which granted him eternal protection.

A Shen Ring amulet. Photo from The Global Egyptian Museum

One of the most significant uses for the shen ring was to contain royal names written in hieroglyphs. In this elongated form, it was called a cartouche. “Cartouche” is actually a French word for cartridge. Apparently Napoleon’s men thought this hieroglyph resembled their ammunition, gave it a fitting nickname, and the word ingratiated itself forever into Egyptology. Nonetheless, protective cartouches were the key to deciphering the Rosetta stone.

A cartouche bearing Ptolemy’s name carved into the Rosetta stone. Picture from The British Museum.

Carving your accomplishments into stelae was a fairly common practice in the ancient world. The Rosetta stone was basically a giant, public “thank you” letter from the Egyptian priesthood to King Ptolemy V. In order to ensure everyone would be able to read it, it was written in three languages: Ancient Greek, the language of the King; Demotic, the language of the common people; and hieroglyphs, the language of the priests. The Ancient Greek and Demotic portions were easy enough to translate, but knowledge of the hieroglyphs had been lost for a thousand years. To make a long story short, identifying the characters of Ptolemy’s name inside of the cartouche was the first real breakthrough in translating the Rosetta stone, which allowed us to later translate many other Egyptian artifacts.

The key point here is that the pharaoh was a semi-divine intermediary between gods and humans. Their names were special – you couldn’t just write it all willy-nilly. You had to contain and protect the royal name by encircling it with a cartouche. As a further detail, erasing those names was sometimes one of the first acts of a new dynasty. If you replaced the name in a cartouche with your own, you not only removed your defeated foe from history, but you could also lay claim to their accomplishments, currying additional favor with the gods for eternity – or at least until the next guy carved his name on top of yours.

The Sun Disc

The sun-disc is portrayed in several areas of Egyptian iconography. It is usually a masculine symbol for the sun, Ra, and sometimes Horus.

In the form of a hieroglyph, the sun-disc was a circle with a point in the center. From this, we have derived our symbol for Alchemical Gold and the Astrological sign for the sun. In the carvings at Karnak, this was used to represent the god Ra. The translated inscription reads “given life like Ra forever.” What a powerful spell this must have been!

Hieroglyphs at Karnak Temple. The Sun-Disc symbol is seen in the second row of the right column. Photo By Olaf Tausch – Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9869957

A very typical portrayal of the sun-disc in artwork is seen in the headdress atop the heads of goddesses. Hathor, a goddess associated with fertility, childbirth, and the cow, was said to give birth to the sun each morning. Accordingly, she wore a headdress of horns with the sun in between. The headdress of Isis was originally the shape of a throne, but as her worship spread during the New Kingdom period, she took on some of Hathor’s roles and began to wear the sun and horn combination.

Statue of Isis holding Horus with horns and sun headdress. Image from The Met Museum.

Statue of Isis holding Horus with throne headdress. Image from The Met Museum.

When Isis wears the horns and sun, it can be seen to represent her dominion over Hathor, the sun, and everything the sun encircled. But she wasn’t the only other goddess to wear it! Sekhmet and Tefnut can also be sometimes seen wearing this headdress.

Like his mother, Horus also wore multiple headdresses. Sometimes, he wore the dual crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, and sometimes he wore a crown of the sun disc. Horus took on so many different forms, it is hard to keep track. He can be seen as a falcon, lion, and crocodile. It was said he was the sky, the sun his right eye and the moon his left. At one point, Horus merged with Ra to become Ra-Horakhty. Along these syncretic lines, Horus was also portrayed as a winged sun disc.

The ceiling at the entrance to the temple of Ramses III features a winged sun. Photo by Olaf Tausch – Own work, CC BY 3.0, Wikipedia

The winged sun disc (that is, a circle with wings) is said to represent power, divinity, and eternity. It was often carved inside temples and over doorways as a sign of protection.

Pharaoh Akhenaton temporarily reformed Egypt’s religion into a monotheism during his reign from 1353–36 BCE. He decreed that Aton, the sun god, was not just a supreme deity, but the only deity. An entire city, called Akhetaton, was built and dedicated to Aton’s worship.

Aton, the supreme Deity, depicted as a solar disc emitting rays, hovering above King Akhenaton and Queen Nefertiti. Image taken from Britannica.

This reformation didn’t last very long, however, as Egypt’s elite seemed to be fairly content with their ideas of polytheism. Shortly after Akhenaton’s death, the city of Akhetaton was abandoned and the old gods were reinstated throughout Egypt.

Almost anywhere you look throughout Egyptian artwork, you can that the sun-disc is a powerfully protective symbol. Reducing it to its simplest form, a circle, has allowed the very shape itself to convey the idea of protection for thousands of years.

Social Circles

The Heb-Sed Ritual is one of the oldest recorded Egyptian celebrations, going all the way back to the First Dynasty (2925 BCE). It featured feasts, offerings, and circular processions to mark off areas of sacred space.

The main point of the Heb-Sed was for the pharaoh to celebrate 30 years of rule and reaffirm his kingship by publicly running an obstacle course. After the first 30 year celebration, it was then performed every three years. Since pharaohs led their armies on the battlefield, they needed to appear strong and youthful. By completing the obstacle course, the pharaoh was rejuvenated by the power of the gods. In the Step Pyramid of Djoser, symbolic boundary markers were placed near the tomb to allow the buried pharaoh to continue performing the ritual for eternity.

First Dynasty carving of Pharaoh Den performing the Heb-Sed ritual. Photo by CaptMondo – Own work (photo), CC BY 2.5, Wikimedia.

It is important to note that textual descriptions of the Heb-Sed ritual state that the pharaoh would “go around” to the boundary markers while running the obstacle course. This verbiage “go around” is also used to indicate when something is encircled. By completing the Heb-Sed, the pharaoh may have been publicly enacting a form of encirclement.

Similar circular processions are mentioned elsewhere, such as in funerary rites and coronations of new pharaohs. One record of a dramatic play even reenacts Osiris’s murder by encircling a character with goats.

It is also possible to see evidence of circles in the games Egyptians played. Mehen was one such game, especially popular during the Old Kingdom period. It is attested both in wall paintings and by archaeological discoveries of the physical game boards themselves.

Mehen Game Board from 3000 BCE. Picture by Anagoria – Own work, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia.

The Mehen board was shaped like a coiled snake and divided into spaces. Although the rules of the game are completely unknown, tokens were used to circumambulate the board. Presumably, players might have started in the center, made their way to the outer ring, and finally returned to the center, symbolic of the soul’s journey through life, death, and rebirth. The name of the game is a reference to the snake god Mehen, but we will talk more about him later.

With the information presented thus far, hopefully it is becoming clear that the circle itself carried the cultural ideas of protection, containment, and boundaries of sacred space to the Ancient Egyptians.

Magico-Medical Papyri

Sekhmet, Isis, Horus, and Thoth have ties to medicine. It should come as no surprise that the top healers in Ancient Egypt were priests. Many sick people would come to their temples seeking aid and their diseases would be treated with a combination of both magic and medicine. If the cause of an ailment was known, like a broken bone, the treatment tended to be nonmagical; however, an illness such as a fever may have been the result of malevolent spirits, so it would require magical treatment. Archaeologists have uncovered collections of spells written on papyrus, specifically for use by a physician-priest for preventing or treating illness. It is from these magico-medical papyri that we can find the earliest examples of ritual encirclement. To protect from the sting of a scorpion, for example, a protective circle would be drawn around the patient. One of these collections, known as the Ramesseum Magician’s Box, even came complete with tools of the trade like a magic wand and carved figurines.

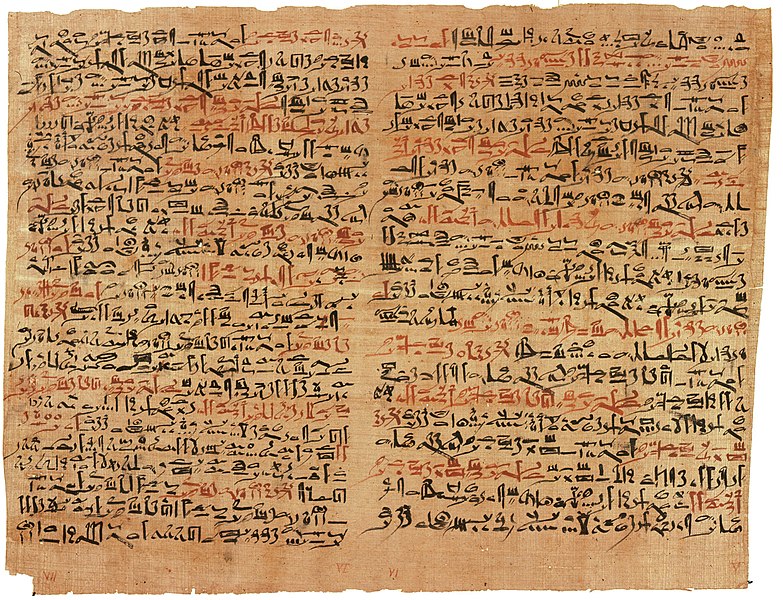

Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus written in hieratic script. Picture from Wikimedia.

The oldest of these collections, dating to the 17th century BCE, is the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus. Among the many spells is one to give protection from a plague-bearing wind. It instructs the practitioner to encircle their home, carrying a “stick of des-wood” (likely a magic wand made from a now unknown tree) while reciting the following incantation:

“Withdraw, ye disease demons. The wind shall not reach me, that those who pass

Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, XVIII 13-15

by may pass by to work disaster against me. I am Horus who passes by the diseased

ones of Sekhmet, (even) Horus, Horus, healthy despite Sekhmet. I am the unique

one, son of Bastet. I die not through thee.”

To sum up this spell: a practitioner, carrying a magic tool, walks in a circle while reciting specified words. Does that sound familiar?

Ouroboros

The name ouroboros comes from Greek words meaning “tail” and “eater.” Today it is a common symbol seen everywhere from alchemy to Gnosticism, but the first depiction goes back to Ancient Egypt, where it decorated Tutankhamen’s tomb sometime in the 13th century BCE.

Image of Ouroburos in The Enigmatic Book of the Netherworld, By Djehouty – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=57397072

The elaborate, gilded scenes carved into Tut’s shrine are referred to as The Enigmatic Book of the Netherworld, a unique version of The Book of the Dead that is seen nowhere else. The form of Ouroboros appears twice, once encircling the head of the pharaoh and once encircling the feet. The accompanying text gives the name “Mehen, the Enveloper” and refers to both the beginning and end of time.

Mehen was a serpent-headed god who defended the sun boat, fighting a daily battle against Apep (also called Apophis, the Destroyer). As the sun made its way across the sky, Apep would attempt to destroy the light, while Mehen would protect it.

Egyptians were very familiar with the cyclical nature of time. In fact, they based their entire calendar on it. Every year, the Nile flooded and receded. Each day, the sun rose and set. Ouroboros reflected these ideas, becoming a symbol for renewal, repeated cycles, and time. To be encircled by Mehen was to be protected for eternity.

The Greek Magical Papyri

At long last, we have finished sifting through a seemingly endless list of art, language, symbols, carvings, statues, and giant rocks, ultimately to arrive at the Greek Magical Papyri, usually referred to as the PGM (from the Latin, Papyri Graecae Magicae). I have listed them at the end because they are the most recent and least ancient, with various parts dating between the 2nd century BCE and the 5th century CE.

Before we get too much into the magick of the papyri, it’s important that we understand the historical time period during which they were written. After Alexander the Great’s conquests in 332 BCE, Greece installed its own kings to rule in Egypt, spreading Greek culture and ideas. The impact of this cannot be understated. For hundreds of years, Greek philosophers had been obsessed with Egypt. Egyptians, on the other hand, were incredibly xenophobic, believing for millennia that they already had the greatest civilization. The end result was a meshing of religio-cultural ideas, the likes of which the ancient world had never before seen. Among other things, this is when the Greek Hermes became syncretic with the Egyptian Tehuti (Thoth) as Hermes Trismegistus, the father of the Hermetic tradition.

The papyri are written by various authors, spanning across hundreds of years, some perhaps by priests and others by professional traveling magicians. A mixture of alphabets was used including Coptic, Demotic, Hieratic, Ancient Greek, and other coded cipher scripts. They first began to surface on the Egyptian art market in the 19th century, eventually finding their way to both museums and private collections. It has been asserted that the surviving texts represent a small portion of a larger corpus, most of which was lost either to time, Christianization, or book burnings. The magical operations described within, which range from elaborate conjurations to simple folk remedies, contain ideas from the Egyptian, Greek, Christian, and Jewish religions. Some of the spells employ the use of encirclement.

PGM V. 370-446

Magical words are written between two concentric circles. This is a spell to bind a named individual against performing a specific action. It is to be written on papyrus and buried at “a grave of someone untimely dead” while saying an incantation.

PGM VII. 300

Words of an incantation form a spiral and encircle the image of an ibis. The exact purpose of this spell is not given, but it is to be written on the left hand with myrrh ink.

PGM VII. 579-90

The image of ouroboros encircles magical words. This is a protective spell to ward against negative spirits, sickness and suffering. It is to be written on a leaf of gold, silver, or tin or on hieratic papyrus. Note the instructions to “add the usual.”

Like medieval grimoires, the PGM read like shorthand notes rather than a full instructional manual. This begs the question as to whether a standard ritual framework, like construction of a protective circle, would have been used by the original operators. Although the practices may have varied significantly between the writers of different collections, I would be inclined to say: yes, there probably was some sort of ritual framework. The inclusion of the phrase “add the usual” smattered all throughout the PGM seems to be especially indicative of this. Even if you and I don’t practice the same magical tradition, I can tell you to recite an incantation after “erecting the temple as usual” and you’ll have a good idea what I mean. Copying scrolls by hand was tedious work; brevity was required; and the papyri were written with the adept in mind rather than the novice.

While not implicitly stated in the PGM themselves, an analysis of Ancient Egypt’s art, culture, religion, and language shows the importance of the circle as a protective symbol. By extension, this would seem to suggest the use of some form of encirclement as a basis for all rituals. As a side note, some modern adaptations of PGM materials do include forming a magic circle as part of the “step by step” instructions.

Conclusions

Whether the Ancient Egyptians were socializing, attending ceremonies, walking, writing, speaking, wearing amulets, treating injuries, or performing more complicated magical operations, they certainly found ways to use encirclement. Do our modern Wiccan circles have roots tying them back to practices in Egypt? Well, it certainly seems like it. Perhaps circles are just convenient shapes. Or perhaps they are so deeply encoded into our collective conscious mind, we can’t help but use them for magick.

Bibliography

- Arkadian, Aerik. Reasons Why I Hate MLA and APA Formatting. Not A Real Book Just Making A Statement Publishing, 2023.

- Betz, Hans. The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation: Including the Demotic Spells. The University of Chicago Press, 1986.

- Breasted, James. The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus. The University of Chicago Press, 1980.

- Brier, Bob. Ancient Egyptian Magic. Quill, 1981.

- Brier, Bob. The History of Ancient Egypt. Narrated by Bob Brier, The Great Courses, 2013.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. A Hieroglyphic Vocabulary to the Theban Recension of the Book of the Dead. Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner, & Co LTD, 1911.

- Davies, Owen. The Oxford Illustrated History of Witchcraft and Magic. Oxford University Press, 2021.

- Griffith, F. Ll. The Demotic Magical Papyrus of London and Leiden. H Grevel & Co, 1904.

- Hall, Manley P. The Secret Teachings of All Ages. Dover Publications, 2010.

- Jung, C. G. Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 9 (Part 2): Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. Edited by GERHARD ADLER and R. F. C. HULL, Princeton University Press, 1959

- Lightbody, David. On the Origins of the Cartouche and Encircling Symbolism in Old Kingdom Pyramids. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd, 2020.

- Ritner, Robert. The Mechanics of Ancient Egyptian Magical Practice. Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2008.

- Roblee, Mark. “Performing Circles in Ancient Egypt From Mehen to Ouroboros.” Preternature: Critical and Historical Studies on the Preternatural 7.2 (2018): 133-153.

Disclaimers: When available, I have linked to Amazon copies of the books I referenced. If you use one of those links, I earn from qualifying purchases through the Amazon Associate program. Many of these books are available for free online, especially on archive.org, but it is nice to have physical copies. In addition to these works, numerous online sources were consulted. Image credits have been given when appropriate and necessary.

Leave a comment