Is that a random jumble of letters? Why, no, it’s a sabbat! Welcome to the most confusing point on the wheel of the year, Lughnasadh.

As I started doing research for this article, I was telling my wife how it was the most frustratingly boring sabbat to write about. There’s no major solar event. There’s no eggs, rabbits, jack-o-lanterns, pine trees, dueling monarchs, or cornucopia. There’s mostly just a general lack of consensus on history and traditions — so much so that it’s hard to make many claims about this holiday. But then I realized that the lack of consensus is exactly what makes it interesting! Before I get into the great amount of disagreement and potential misinformation surrounding Lughnasadh, let’s look at why it’s important. For starters, it’s a harvest festival that celebrates grain. Grain makes bread, bread sustains life, life is important. It’s also commonly associated with Lugh, the Celtic sun god, who is a pretty cool dude.

Alright, did you get all that? Good. That’s about where the certainties end.

Spelling and Pronunciation

For a good starting point of confusion, we can’t all seem to agree on one proper spelling. Most commonly, I see the word written as Lughnasadh, but alternatives include Lúnasa, Lughnasa, and Lughnassa. I’m not an expert on Old Irish or Old Gaelic, so these spellings are all as equally correct to me as they are equally wrong.

Since we like to spell it so many different ways, obviously we can’t all agree how to pronounce the word either.

Pronunciation Argument #1

–The Witch’s Wheel of the Year by Jason Mankey

Lughnasadh = "Loo-NAH-sah"

Pronunciation Argument #2

–Lughnasadh: Rituals, Recipes & Lore by Melanie Marquis

Lughnasadh (Pronounced LOO-nah-sah)

And then, of course, I’ve heard stranger attempts like LUG-nuh-sad, but I think most of us can at least agree that the gh and dh are silent.

For what it’s worth, my personal pronunciation stresses the first syllable, rather than the second, and I typically write it as Lughnasadh. If you happen to catch a different spelling within this article, it’s just because my spellcheck doesn’t like any of them.

Dates and Aliases

Lughnasadh is celebrated every year on August 1. Or August 2. Or… July 31. But August 1 is definitely the most widely accepted date.

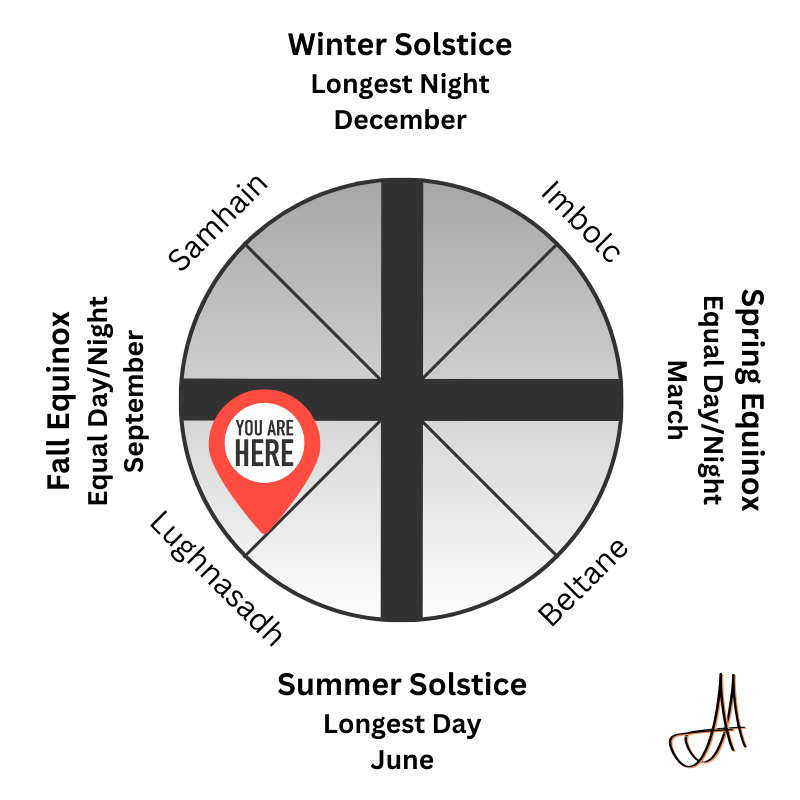

Don’t worry. If you’re lost, just refer to the locator dot on the wheel of the year.

Other names include Lammas, Garland Sunday, Bilberry Sunday, Mountain Sunday and Crom Dubh Sunday.

Lughnasadh sits between Summer Solstice (Litha) and Fall Equinox (Mabon). By the Celtic calendar, this date marks the beginning of Fall. It is the first of three harvest festivals (Lughnasadh, Mabon, then Samhain) and is celebrated for the harvest of grain.

Meaning

Some sources claim that Lughnasadh is a contraction of Lugh, the sun god, and -nasadh, which means “a feast or assembly.” Is that for real? I’m not sure. But it makes sense when you think of a sun god being celebrated at the grain harvest.

Other sources claim that it is perhaps a contraction of Lugh and nas, which means “death.” Well, that also makes sense if we’re celebrating the death of a god around harvest time.

Can I propose we take the best of both worlds? We’re assembling to have a feast, celebrating the god who is becoming a sacrifice. But more on that later. For now, let’s get some general associations out of the way.

Want to hear about future posts? Subscribe to get notifications delivered straight to your inbox.

Associations

- Colors: Yellow, gold, orange, brown, green, red

- Flowers: Sunflower, marigold, or anything locally in bloom

- Crystals: Carnelian, tigers eye, citrine, green aventurine

- Herbs: Rosemary, fenugreek

- Foods: All grains. Alternatively, anything harvested locally at this time

- Deities: Lugh

- Activities: Baking bread

- Instruments: Drums

Myths & Traditions

In the words of Jason Mankey, “So many of the sabbats have stories upon stories, Lammas has bread?”

Baking bread is not an altogether exciting thing to do, but it’s a pretty universally accepted tradition for Lughnasadh. After all, we’re celebrating the grain harvest.

Some people also make corn dollies to celebrate the spirit of harvest.

Handbell Corn Dollies. Public Domain. Image Courtesy of Wikipedia.

But wait, why do these corn dollies appear to be made out of grain… and not out of corn?

We’re already full of confusing words today, so let’s start with a disambiguation.

Corn (Maize)

Also Corn (Wheat)

You know? I love etymology, but this one is complicated. I hope you’ll settle for a summary. In the United States, we usually use the word corn to refer to maize. But in most of England, corn meant wheat. It’s thought that maize originated somewhere in Mexico thousands of years ago. Think about that for a moment. That’s pretty far away from the Celts. When we talk about corn dollies here, we’re really talking about wheat dollies.

According to legend, folks tended to think that the spirit of the harvest dwelled within their fields. Nobody really wanted to be responsible for offending that spirit, so everyone would take turns throwing their sickles at the last sheaves. Those final pieces of wheat, once cut down, would be fashioned into a corn dolly, where the harvest spirit could safely dwell until the next season.

If you ask me, that’s a pretty cool tradition. Most people don’t have wheat fields anymore… and here in Florida we don’t really have seasons either, but you can still make a corn dolly to honor the wheel as it turns. They can be as simple or as complicated as your grain-weaving skills allow. For what it’s worth, you can make them out of corn husks (maize) as well.

The God and Goddess

What are the god and goddess doing around this time around this time of year? Well, if you follow the cycle, the goddess is pregnant. This image of fertility is reflected by the harvest season, where the earth itself is bountiful.

The god, on the other hand, is getting ready to become the sacrifice that sustains that fertility. By Summer Solstice, the Sun God has assumed responsibility to protect the land, the people, and the kingdom. At Lughnasadh, that responsibility extends further into willing sacrifice. He becomes the Corn King, knowing full well that he will die at Samhain.

Why Lugh is Actually a Badass

Lugh, the namesake of this sabbat, is a pan-Celtic sun god. He is sometimes equated with Apollo or with Mercury, so right off the bat he’s got my attention. His name literally means “the shining one,” although this specific etymology has been debated.

As far as his parentage goes, Lugh was the son of Cian and Ethniu, but was fostered by Tailtiu, who was Queen of the Fir Bolg.

Within the Tuatha Dé Danann (the “tribe of Danu” — a pantheon in Irish mythology), Lugh was a king, warrior, master of the arts, and skilled craftsman. He had mastery of so many different disciplines that sometimes he is associated with skill itself.

Unfortunately, it’s rather hard to find clear depictions of Lugh from the ancient world. He is frequently described as a tall, young man, but varying sources will give different specifics as to his appearance. He does have a dog, though — a loyal hound named Failinis.

A modern statue of Lugh — from Amazon

According to one legend, Lugh sought entrance to Tara (basically, the land of the kings) and was stopped by the gatekeeper. At this time, only the most skilled people in the land were allowed to enter. The gatekeeper challenged him, asking him why he should be admitted. With his long list of skills, Lugh thought this would be a quick answer, but the reality turned out to not be so easy. The conversation might have gone something like this:

An Except from “The Coming of Lugh” found in Irish Lyrics and Ballad by James Dollard

Three times he struck the brazen door, whose guard

Spake from within: "No man can enter here

But one who is the master of some craft;

What can you do?" "I am a carpenter."

And answer made the guardian of the door: —

"We have a carpenter already here,

Luchtar the son of Luachaid." Then said Lugh:

"I have the craft of smith." "We have within

Colum, a smith, and master of his trade."

"I have the craft of Champion," pleaded Lugh.

"We have here Ogma, Champion of the World."

Then Lugh: — "I am a harper of renown."

"We have here Abhean, son of Bicelmos,

In far-off Toomoon of the Fairy Hills

Chosen by all the men of the three gods."

Lugh spoke again: — "I have the noble craft

Of poet and historian." "We have here

Ere son of Ethaman, a poet true."

Said Lugh: — "I am a wizard and physician."

"We have the great physician Dian Cecht,

And wizards and magicians by the score."

"I have the craft of cupbearer," said Lugh.

"Nine cupbearers we have within the dun."

"I am a brazier working brass and gold."

"We have the famous brazier, Credne Cerd."

Then Lugh cried out: — "Go, ask your Danaan king

If he has ONE man who knows all these trades.

If so I will not enter." Then went off

The Keeper of the Door to Nuadha; —

"There is a wondrous youth who stands outside;

As the Ildanach, Master of All Crafts,

He seeks admittance." "Open then to him,"

Said Nuadha, "I wish to see this youth."

Lugh went down his massive list of skills, naming carpentry, smithing, poetry, magic, medicine, and more, but the city already had people who possessed these talents. Frustrated, he demanded to know if there was one single person who could do all these things — a master of all. Upon this merit, he was finally allowed entry.

Based on my understanding of Celtic mythology, there was no patron of music, but that is because all of the gods played music. With this in mind, and with his command of poetry, I like to think of Lugh as a master song-writer. But on top of that, he’s a physician and a wizard. Oh, and he wields an unstoppable spear.

Yep. Lugh is a badass. I’m pretty certain he’d have no trouble mastering the Lughnasadh tradition of baking bread. In fact, he’d probably bake an unstoppable loaf.

Lammas

Now that we’re talking about baking bread again, I suppose it’s a good time to talk about Lammas. Lammas means “loaf mass.” It’s a Christian holiday celebrated on August 1.

Traditionally, people would bake bread using flour from the first fruits of the harvest season. A loaf would be brought into the church, where it would be blessed by a priest.

This holiday ties the Christian church to the agricultural wheel, but ultimately it’s just another example of Christianity assimilating local practices to make conversion more “palatable” for pagans.

-some priest, probably like 1500 years ago

"Yeah, yeah, you folks can still bake your bread and everything, but now I'm going to bless it in the name of Jesus instead of Lugh."

Shakespeare also mentions Lammas in Romeo and Juliet.

-Romeo and Juliet by WIlliam Shakespeare

"Even or odd, of all days in the year,

Come Lammas-eve at night shall she be fourteen."

I bring up this point just to illustrate the fact that, at least during the 16th century, “Lammas” was common nomenclature. Beyond Shakespearean references, this was also a time of year to open lands, hold festivals, elect officials, and pay rent. Everyone would have been familiar with the word.

Conclusion

All snarkiness aside, Lughnasadh (or Lammas, if you prefer) is an important spoke on our modern wheel of the year. Each of the Greater Sabbats (Imbolc, Beltaine, Lughnasadh, and Samhain) mark energetic shifts that are mirrored both in nature and our own psyche. If you can’t figure out anything else to do, you can always build a bonfire, but harvest festivals are also a perfect time to be grateful. Give thanks to the earth (the goddess) for the bounty she is providing or to the sun (the god) for his imminent sacrifice.

Bread might seem simple and boring by today’s standards, but ancient people depended on it to survive. Remember that agriculture itself is a skill. I think Lugh would be especially proud of any permaculture farmers today. Planting seeds, nurturing plants, and harvesting crops are not easy tasks. If grain doesn’t interest you, try incorporating something into your Lughnasadh ritual that is harvested locally in your area during the month of August. Here in Florida, that includes mangos and passion fruit, so maybe we’ll have passion fruit punch during cakes and wine!

Every segment on the wheel of the year has been assimilated and reassimilated, filtered through different cultures and belief systems. It doesn’t necessarily matter what the ancient Celts did thousands of years ago — what matters is celebrating it in a way that makes sense to you today. Personally, I’m a fan of maintaining at least some elements of tradition, so I like the dolly-making and bread-baking. But as long as you pay attention to what the sun and the earth are doing, you’re free to make up your own celebrations!

Although it seems so much simpler at times to just say “lammas,” I think I’ll stick with “Lughnasadh.”

Happy Lughnasadh!

What are you doing all the way down here? Congratulations for reaching the end of the article. You may notice that I occasionally include Amazon referral links in my posts. If you use one of those links to make a purchase, Amazon pays me a small commission. Thus endeth the fine print.

Leave a reply to Ashley Cancel reply